By Frank Sargeant

Frankmako1@gmail.com

Just when the smalltooth sawfish appeared to be on the comeback trail, “spinning disease” has descended on the south Florida population.

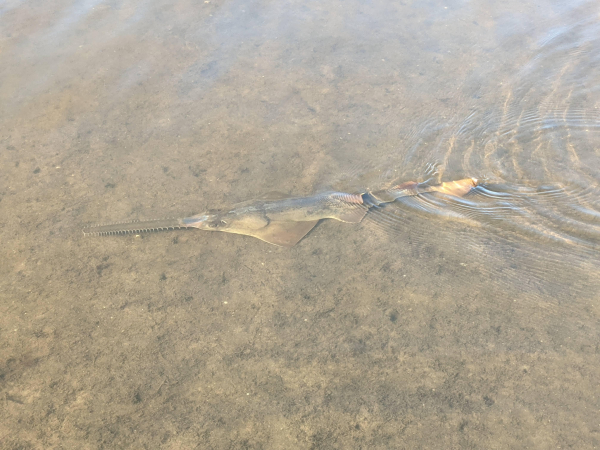

The smalltooth is one of the most endangered fish in U.S. waters, with only a fragmentary population remaining in southwest Florida and the Everglades until recent improvements. The species gives birth to live young, with a maximum of only 20 “pups”, so the population is sensitive to anything that removes many of them before they reach reproductive age. They’re closely related to rays, rather than the bony fishes we all pursue.

Now, those gains seem tenuous at best, as 105 of these unusual creatures have been discovered dead or dying after an odd spinning or whirling malady that seems symptomatically somewhat similar to the whirling disease that has decimated some cold water trout hatcheries over the last decade.

The malady has been observed in tarpon, pinfish, grunts and other flats species as well in recent months. Scientists and anglers have recorded nearly 200 spinning incidents involving more than 30 species, but the biggest concern is for the smalltooth sawfish, because the breeding population remains only in southwest Florida, roughly from Charlotte Harbor through the Keys. They were once found Gulfwide as well as along the Atlantic up to the Carolinas.

Interestingly, when the spinning fish are put in “clean” saltwater, the spinning behavior soon stops, so it’s something in the habitat or the water, but what remains to be seen.

But what can be done with a malady like this, which has no immediately evident cause?

Researchers with the Florida Fish & Game Commission have found no signs of a communicable disease. There’s no red tide in the areas where the affected fish have been found. No issues with oxygen, salt levels, pH or water temperatures, either. There’s some speculation, but not much proof yet, that the organism that causes ciguatera or fish poisoning might have some role.

Mote Marine, a private non-profit which runs a large aquarium and marine education facility in Sarasota, has volunteered to assist in studying the malady, and also in holding sick fish for treatment. Mote was founded by marine scientist Eugenie Clark in 1955 and expanded and moved to Sarasota in 1960 by philanthropist Bill Mote, an avid saltwater fisherman.

One thing the Mote effort might do is simply form a refuge for as many sawfish as can be located—but of course finding relatively rare fish, even fairly large ones, is a real challenge in the hundreds of square miles of shoreline and bayou country of southwest Florida and the Everglades.

Sawfish are not aggressive toward humans, but they are definitely very dangerous. When hooked, they start swinging that many-pointed “saw” in every direction wildly, and if you get hit, it’s multiple stitches at best. When we used to accidentally catch a few small ones—2-3’ long--while snook fishing with scaled sardines in the Everglades City area, we tossed a towel over the eyes and saw, and this made it possible to handle them without getting hurt.

Of course, for commercial fishermen who catch a 12-footer in their nets, handling is a much bigger problem—these giants can be truly dangerous when they start swinging that giant saw, and historically net fishermen simply shot them before trying to disentangle them. Handling the big ones, for research or treatment, is still a huge problem.

Unfortunately we are probably at the beginning of the spinning fish issue—these things don’t often go away on their own, especially when found in diverse areas at the same time. For the time being, anglers in southwest Florida and the Keys can help by keeping a sharp eye out for any sick fish of any species and reporting it to Mote at (941) 388-4441.