Valentine's Day isn't just for humans. It's also a chance to marvel at the diversity of hearts throughout the animal kingdom, especially beneath the waves.

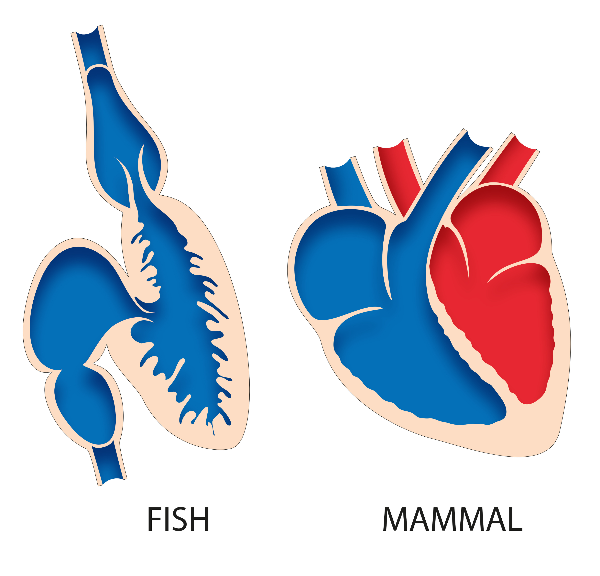

Fish hearts aren't simply slower versions of ours; they're finely tuned engines shaped by cold water, long migrations, sudden bursts of speed, and life in low-oxygen environments. Unlike mammals, most fish have a two-chambered heart—one atrium and one ventricle—arranged in a loop. Blood flows from the heart to the gills to collect oxygen, then out to the body and back again. But simple doesn't mean boring.

Fish hearts aren't simply slower versions of ours; they're finely tuned engines shaped by cold water, long migrations, sudden bursts of speed, and life in low-oxygen environments. Unlike mammals, most fish have a two-chambered heart—one atrium and one ventricle—arranged in a loop. Blood flows from the heart to the gills to collect oxygen, then out to the body and back again. But simple doesn't mean boring.

Off North Carolina's coast, bluefin tuna move like living torpedoes. Built for endurance and speed, they have large, muscular hearts capable of powerful contractions. In colder waters, their heart rates can climb toward 200 beats per minute to meet the oxygen demands of long migrations and explosive chases.

Here's the twist: bluefin are partially warm-bodied, keeping parts of their muscles warmer than the surrounding water while their hearts remain at ambient temperature. Even so, their cardiovascular systems perform efficiently from chilly Cape Hatteras waters to warmer offshore currents.

Closer to shore, species such as flounder, red drum, and striped bass live differently. Their heart rates are slower, rising when feeding or escaping predators. Cold winter waters can slow rhythms dramatically, which is one reason why sudden temperature swings can stress coastal fish species.

Some marine creatures take things even further. The deep-sea hagfish have a primary heart plus several accessory pumping structures that move blood through their low-pressure circulatory system. Octopuses have three hearts—two for the gills, one for the body.

Heart design tells a story of habitat, temperature, and survival. So while candy and flowers steal the spotlight this Valentine's Day, remember, some of the most remarkable hearts are beating beyond the shoreline.