The first Hawaiians are thought to have arrived at the mid-Pacific islands through dead reckoning and a knowledge of ocean currents and swell patterns.(Bing AI)

For those of us who have become “temporarily disoriented” either on the water or in the woods, modern hand-held GPS has been a Godsend.

Though, of course, it only works if you use it.

Once, on Tampa Bay in my home waters where I had fished hundreds of times, I decided that the little bit of fog that slid in along the South Shore was not enough to get me turned around after a good morning of wadefishing for reds. I cranked up, headed for where I “knew” the deep water was, and promptly ran aground so hard that I had to sit there for three hours and wait for a rising tide to float me off. The GPS pointed this out to me when I turned it on, too late.

I’d add to that numerous times of getting turned around in the woods on turkey and deer hunts, though fortunately I always managed to sort these out soon enough to spend the night in the cabin.

Be that as it may, modern GPS is usually a sure thing for keeping yourself oriented.

But how did the early explorers find their way?

The compass was a huge help—first used for navigation by the Chinese in about 1200 AD, the originals were simply magnetized needles through a cork floating in a bowl of water.

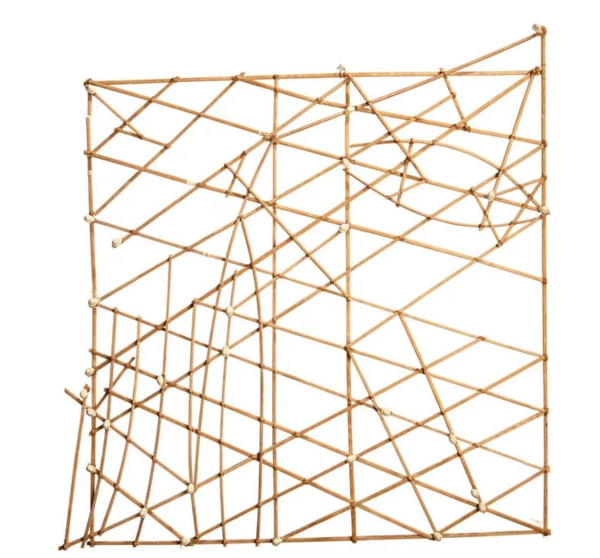

Polynesian Stick Chart served as a visual reminder of oceanic swells and waves for early navigators of the South Pacific. (U. of Hawaii)

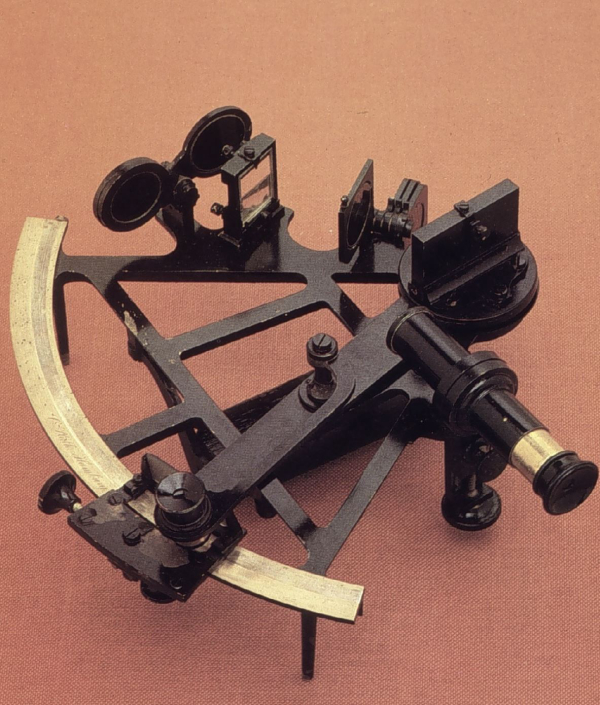

The sextant came along about 500 years later, used in combination with tables of where the stars were located on a given date for more precise navigation.

But what about before these tools?

Hawaii sets in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, some 1200 miles from the island chain where the Polynesians who first discovered it set sail. And while the first to get there might have been lucky—and we don’t know how many voyages set sail and never hit anything but more water, and perished as a result—after the islands were discovered and reported back to the home islands, more of these incredible sailors made the voyage and hit the islands again and again.

How were Polynesians able to navigate precisely across thousands of miles of open ocean more than 1,200 years ago?

We’ll never know for sure, but based on traditional knowledge handed down among the islanders to the modern era, there seem to be several commonalities.

1. They followed the stars. Maintaining a more or less steady course on a sunny day is not tremendously difficult because the sun consistently appears to follow the same east to west path as the planet spins, though the angle with the horizon changes with the seasons. By night, the constellations of stars provide the same directional aids for those who know where to find them. (Of course, neither of these aids work in cloudy or foggy weather.)

2. They followed the birds. While some seabirds survive for weeks far from land, all of them eventually return to solid terra firma. By heading in the direction birds head at sundown, the intrepid navigators would improve their odds of hitting land.

3. They followed volcanic smoke signals. It’s likely that the islanders who first found the Hawaiian chain were guided from many miles at sea by the smoke plume from the islands massive (and still percolating) volcanoes at Mauna Loa and Kīlauea. The mountains themselves are visible many miles at sea due to their 13,000’ height—they occasionally get snow up there!

4. Most amazingly, they followed the swells. For the islanders forced to learn swell patterns to survive, the persistent shape and direction of prevailing seas and swells formed a method of steerage that put them more or less in the ballpark of land masses they were attempting to hit. They built string and stick charts to more or less mimic the interaction of the seas and act as crib sheets.

The Sextant assisted navigators after it was invented about 1759, allowing an accurate way to navigate by the stars. (Wikimedia commons)

In some areas, the method is surprisingly accurate—some modern practitioners can still unerringly find remote atolls simply by “feeling” the ocean over hundreds of miles. (Though, these days, you can be pretty sure most of them carry a GPS and a compass as a backup!)

There’s no question it’s still very easy to get turned around at sea or in the woods, and sometimes those handy little pocket GPS units run out of battery about the same time your cell phone does. You may never be able to navigate by the shape of oceanic swells, but a little awareness of celestial navigation could be mighty helpful when everything else is letting you down.

— Frank Sargeant

Frankmako1@gmail.com